The discovery of Buddhism in the West has opened doors to practices such as meditation, yoga, the notion of happiness, and also the philosophy that allows us to re-question our own. We’ve come to realise that there are many similarities between the East and the West, particularly in terms of human values. The common thread in all this is self-awareness, the scope and responsibility of our actions, the elimination of suffering, and so on. Believing that elsewhere will provide better answers to our questions, we forget that we have also had wise men, enlightened men perhaps.

Could Socrates be a Greek Buddha?

Our elsewhere is here and there at the same time, finding the best balance between our roots and our projections.

When I was about 10, I remember asking myself a very specific question: who am I? That’s right: who are we really?

Around the age of 13-14, I first discovered Buddhism through my father’s books. It was at the age of 20 that I pushed open the door of my first Buddhist centre, wanting to discover the practice that leads us towards ourselves. My first steps were taken in a Tibetan temple for a few years, then in a Zen dojo for 10 years. All this was punctuated by several trips to Asia. Always with this thirst to discover who I am and how to eliminate suffering. What bothered me the most was the exoticism and the desire to escape from reality that some people seemed to be looking for, like an escape from the suffering and demons in each of us (without that being a criticism).

A short while ago, I followed the teachings given by Trinlay Rinpoche who came to the Yeunten Ling Buddhist Institute in Huy to comment on and explain Shantideva’s book, ‘Bodhicaryavatara, The Path to Enlightenment’.

In particular, the book explains that each practitioner must follow a preparatory path before reaching enlightenment. A metaphor is that before dyeing a cloth, it is necessary to wash it of the stains it carries.

These preparations are designed to develop the sincerity of the practices, by developing the right attitude without falling into devotional ways.

Shantideva explains that through the preparatory practices, we become increasingly aware of our surroundings. We become aware of our beliefs, our inner fictions, our illusions.

For example, the notion of ownership is a fiction: this house belongs to me, but in reality it belongs to the bank. In our garden, we can say: ‘these flowers are mine’ and the bees have also taken possession of them.

Everything is relative.

So it’s possible to take a step back and see that the I, the ego, forces and pushes itself at certain times. If we take a step back and distinguish between ‘I’ and ‘self’ (what lies deep within each of us, beyond and within the ego), we can see how we sometimes run around like headless chickens, or that ‘I’ is thanks to others.

As we go along, we become more aware, we see more clearly what is going on within us and around us.

We see that attachment is very often confused with appreciation: I like this, I want it even more. Something that is appreciated is subject to attachment. Yet non-attachment is not disinterest, rejection or hostility. We can appreciate without seeking to repeat or want more and more.

This is how we begin to differentiate between love and desire. Desire is a form of attachment. The other is not a possession. If we truly love, the love we bear goes hand in hand with the freedom we share.

Wealth and notoriety can be the results of our actions, but seeking or forcing wealth and notoriety can be problematic.

And so on.

These preparatory practices highlight the ego and the fictions it tells, and we gradually emerge from the illusions it imposes on us.

Listening to Trinlay Rinpoche, a link appeared to me with the Hannya Shingyo, the heart sutra which is, I think, a fine example of the Middle Way. I love this middle path, which gives me the image of a tightrope walker, seeking the right balance between the extremes he holds in his hands, without falling into either. For me, any spiritual practice must or should fit in as well as possible with society and our daily lives. A spiritual practice should not seek to extract itself from our society; on the contrary, it should lead us to immerse ourselves more fully and better in it.

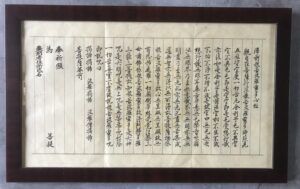

The Heart Sutra

In Japan, the Heart Sutra (the Hannya shingyo recited in Zen) has been adopted as a key text. The heart does not refer to our blood pump or our emotional centre. The idea of the heart refers to the essence, that which is deepest, and to feelings, the awareness we can have of them and thus perceive reality more clearly. Sometimes this sutra is presented as the sutra of the essence of wisdom. It relates a discussion between the Buddha and one of his close disciples. Without going into the whole text, here is an example extract:

[…]Shapes are no different from emptiness, emptiness is no different from shapes. Forms are empty, emptiness is forms. The same is true of perceptions, mental constructs and consciousness. Since all these elements have the aspect of emptiness, they neither appear nor disappear, they are neither tainted nor pure, they neither grow nor diminish. Thus in the void there are no forms, sensations, perceptions, constructions or constructs. […] (1)

Let’s explain something:

Emptiness is a relative notion: a cup can be empty of tea and full of air.

By ‘emptiness’, we don’t mean ‘the absence of’ but ‘the as yet unexpressed potential’ and ‘the emptiness of all interdependent relationships’. To give a clear example of interdependence, we can take a table. This table is a concept: we took a top and four legs, and called it a ‘table’. This table must have been made by a carpenter. The wood he chose came from a tree that had grown thanks to the quality of the soil and the climatic conditions, etc.

Making the link with the sutra of the heart, when we become aware of our beliefs, we can realise the interconnections of everything we carry within us, linked to our upbringing and our experiences. We then see that there is no such thing as belief or non-belief, illusion or non-illusion. There is a path which, if followed with sincerity, will become clearer and clearer. There is nothing to attain, nothing to expect, nothing to seek. Just a return to what was already there.

The Buddha illusion

Our society has cast the Buddha as a supranatural being, a deified man. Nietzsche developed a similar notion with the superman.

I think it’s important to remember the historical context and roots of Siddharta Gautama Buddha: he was born a man and a prince. He was born a man and a prince. He grew up in a world of plenty, with an extensive education. He certainly stripped himself bare, but he never extracted himself from the societal realities that surrounded him (he wanted to see beyond his walls and embrace and experience other realities. He sometimes withdrew from the world and its people, only to return to them again and again. After testing asceticism, he even advised conscientiousness and temperance.

For me, Buddhism is not practised in a temple or a Zen dojo. These are the places where its values are taught and remembered. The teachings need to be put into practice in the world, especially outside the protected and special places that are temples and dojos.

For me, the worst and perhaps the best place to practise is in the car, which cuts us off from others. Everyone in their own car, racing towards their own goal, but together on the shared road. Just like in life.

The essence of the practice lies in the mental attitude, the disposition of the mind.

You have to practise relentlessly with constancy and lightness, with strength and detachment, for the pleasure of the exercise without expectation.

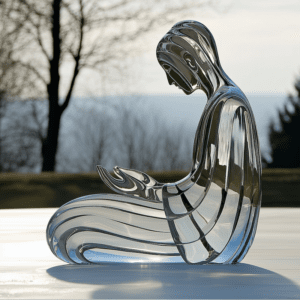

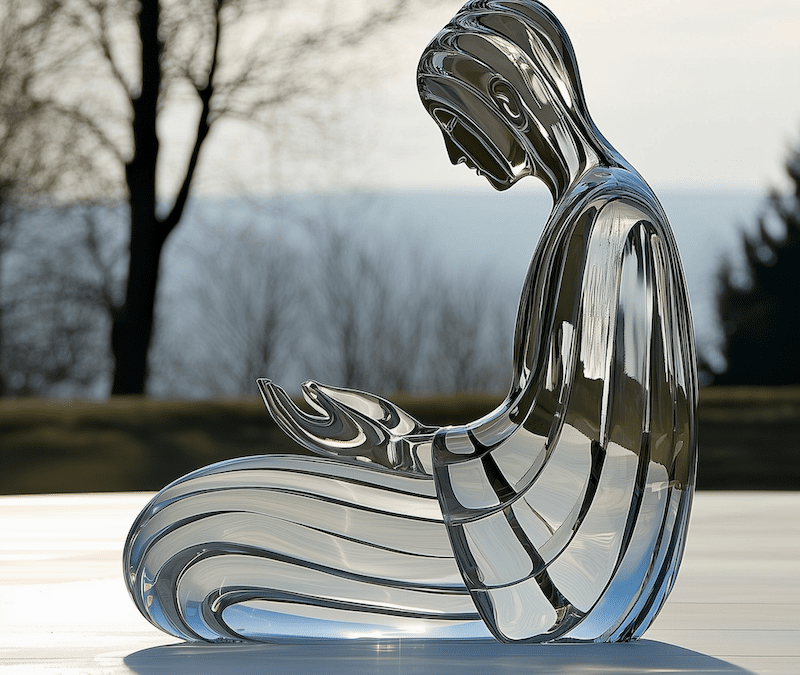

Awakening happens little by little. It is not an explosive illumination, it is a refinement, like polishing a stone to make it shine. Awakening to reality does not change man in his form but advances him in his function.

“Man achieves enlightenment as the moon dwells in the midst of water. The moon is not wet, the water is not broken. However wide and great its brightness, it dwells in a tiny sheet of water. The whole moon and the whole sky remain as much in the dew of a blade of grass as in a drop of water. That the awakening does not break man is like the moon that does not pierce the water. That man does not hinder awakening is like the dewdrop that does not hinder the moon in the sky.” (2)

(1) extract taken and translated from Hannya Shingyo

(2) quote from the Genjô-kôan in Yoko Orimo’s book “Comme la lune au milieu de l’eau”

Recent Comments