For some time now, I have noticed a certain dichotomy sometimes going as far as splitting concerning the practice of shiatsu and its breeding ground. These exchanges inflame futile ideological debates but the questioning remains a rich teaching exercise.

The root of shiatsu

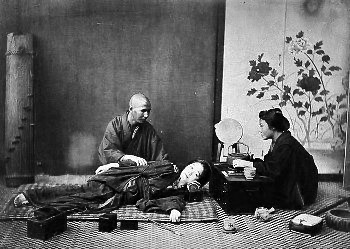

I discovered shiatsu in 2000. I then practiced aikido and Zen meditation. I had the chance to start my lessons directly with Kawada Sensei. In his classes, Kawada Sensei spoke to us very regularly about philosophy, he told us personal anecdotes, explained historical realities. Casually, he opened small windows on the contexts that allowed shiatsu to take root. I put this word in the plural because there is no root of shiatsu, there is no shiatsu.

All this is rich and complex, I refer you to the book “Shiatsu, a Japanese art” by Stéphane Cuypers published by Les éditions du Renard Blanc.

Here, I will take the height and try a global vision, therefore fragmented.

Late 18th century Japan was coveted by Westerners. It was the moment following the transition from tradition to modernity: some samurai clung to their katana, others preferred the musket. The Dutch and the Americans wanted to trade, the Portuguese wanted to evangelize. There reigned a double spirit: openness to the West and preservation of traditions. Openness to the West, science, material development. Preservation of traditions in the Buddhism-Shintoism balance.

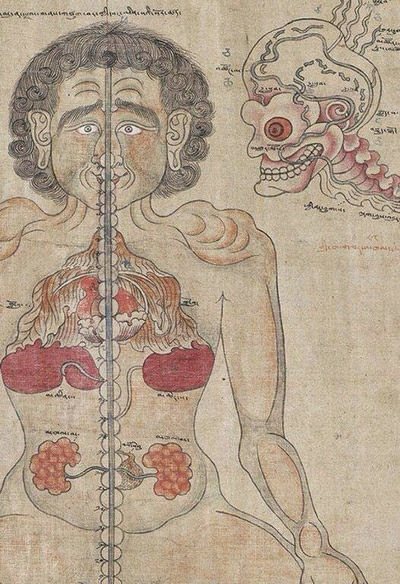

Certainly, some 4 centuries earlier, there had already been exchanges with China. It is a perpetual movement of exchanges. The breeding ground is rich, there are also traces coming from Tibet, to follow.

They still retain this ability to digest and integrate Western principles and add them to their reality without losing their roots.

To realize this, just go to Japan and see how Buddhism and Shintoism are part of life.

We in the West want to study this as theoretical concepts. These are not concepts, it is inherent in societal reality.

Scientific realities

At home, the science movement has established the notion of scientific evidence: everything must be verified, measured, visible, coherent and consistent.

We are entitled to ask ourselves the question: is this the only way to look at science?

In Asia, the oral tradition is important. There are of course the writings but these keep only the general lines. It is enough to see how even today the traditions and empirical practices are transmitted from master to students, i shin den shin (this is a subject to which we can return because it requires a little development).

Not long ago, I read the report of a conference by the Dalai Lama’s doctor. The Tibetan medical approach can shake us up by its point of view. We find at home this approach that is noticeably common in Chinese medicine, in homeopathy, naturopathy, essential oils. In this lecture, he defines quite precisely the nervous system as it was discovered in Tibet and that we find at home. A speaker asks him the question of when and how it was discovered, if there was dissection. The nervous and blood systems were discovered around the 8th century, he replies, without the need for dissection. He specifies that the scientific approach of the Tibetans at the time could be very different from our approach and our ways of thinking and doing. The different nervous and blood systems could be determined by researchers who immersed themselves in very deep states of meditation and could thus feel and explore their physiology. One cannot say that this approach is totally etheric or heretical if I play with the words: in the 8th century, it was the Church that dictated these scientific canons.

This answer and this approach can raise questions, call out or cry out, it invites us to ask ourselves questions about plural approaches. We can also question the structure in which we grow up: is this the only way to look at things?

Yes, and yet it turns!

What is frankly interesting is that these discoveries in the 8th century are incredibly precise compared to our current knowledge.

In short, we must accept that there can coexist different ways of thinking and envisioning life (whether scientific, philosophical, economic, etc.), that other approaches are not to be rejected. Let’s show some mental flexibility.

Our practice of shiatsu

To enrich our practice and not reduce it to a simple mechanical repetition, it is instructive to delve into the texts which are the soil of the culture which gave birth to shiatsu.

Not wanting to understand this would be like eating a hydroponic strawberry and being convinced to fully taste the fruit.

The texts that best structure this are actually in Buddhism. Not seen as a religious movement but as an empirical science that explored the human psyche. It also allows us to question our place as therapists and our human reality. Reading and reflecting on concepts such as impermanence, suffering, consciousness among others helps to illuminate our practice to understand what may exist behind the technique. The desire to improve one’s gestures, to go further in technique will be enriched by these readings which will develop the art of nuance and understanding of what is at stake behind the symptoms. Technique is nothing without theory and vice versa.

Practice and reflection are balanced for a correct understanding of things.

Good practice! Good readings!

Recent Comments